The story so far: The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics celebrates a monumental achievement: the observation of macroscopic quantum tunnelling. This phenomenon, where particles mysteriously pass through energy barriers without sufficient energy (imagine tunneling through a mountain rather than climbing it), is well-known in the subatomic world. However, laureates John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis demonstrated that this ‘quantum weirdness’ can also manifest in larger, visible superconducting circuits. This groundbreaking discovery promises to revolutionize how we process and utilize information.

What Exactly is a Josephson Junction?

At the heart of the trio’s award-winning research lies the Josephson junction—a simple yet profound device consisting of two superconductors separated by an incredibly thin insulating layer. Their core question was whether a collective property of this circuit, specifically the phase difference across the junction, could exhibit the behavior of a single quantum particle. Their experiments yielded a definitive “yes,” revealing both macroscopic quantum mechanical tunneling and distinct, discrete energy levels within the circuit.

A schematic illustration of a single Josephson junction. A and B are two superconductors; C is an ultrathin insulator.

| Photo Credit:

Miraceti (CC BY-SA)

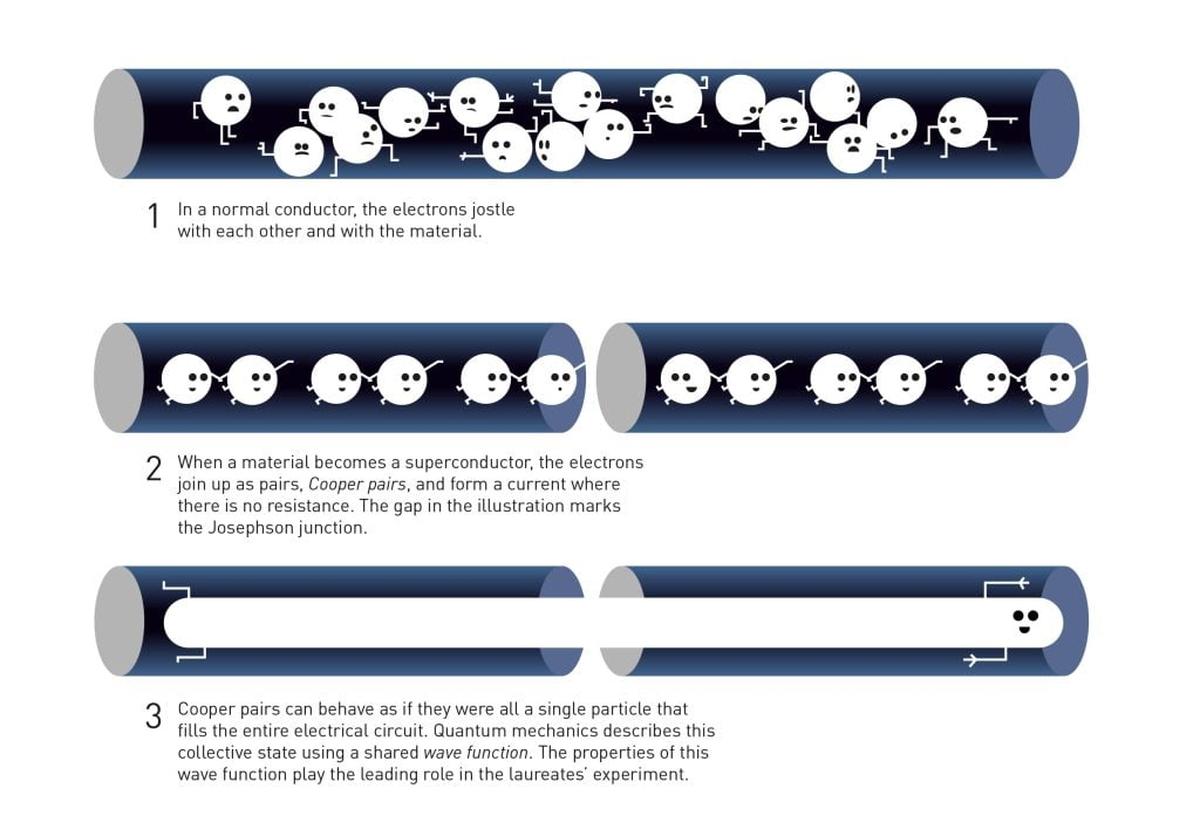

Within a superconductor, electrons form pairs and flow without any resistance. In a Josephson junction, the key variable is the “phase difference” of the superconducting order parameter—a grand-scale property shared by countless electron pairs, defining the system’s quantum state. Theoretical models predicted that the current flowing through the junction would depend on this parameter, with the phase difference evolving over time based on the voltage applied across it.

When the research team introduced a sufficiently small current into the Josephson junction, they observed that the flow of electron pairs became stagnant, resulting in no measurable voltage. In the realm of classical physics, this state would be permanent—the electrons would remain indefinitely trapped. However, quantum mechanics dictates a different reality: the current possessed a slight probability of abruptly “tunnelling” out of this trap and flowing freely on the opposite side, thereby generating a detectable voltage.

The Challenge: Why Was the Circuit So Fragile?

Throughout the early 1980s, various research teams attempted to detect this elusive quantum tunneling. Their method involved adjusting the current and noting the point at which the junction registered a voltage. If electron pairs were merely escaping due to thermal energy (like particles “hopping” over a mountain when heated), then progressively cooling the device should increase the current needed to generate a voltage. Conversely, if true quantum tunneling was occurring, the rate at which electrons crossed the barrier would eventually become independent of temperature.

Despite the seemingly straightforward experimental design, a significant hurdle emerged: preventing stray microwave radiation from disrupting the delicate circuit and skewing the data. To achieve the desired temperature-independent behavior, the researchers had to meticulously minimize and precisely characterize all environmental noise.

The Berkeley team, spearheaded by Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis, ingeniously tackled this challenge by completely overhauling their experimental setup to eliminate interference from stray signals. They implemented specialized filters and robust shielding to effectively block undesirable microwaves, while simultaneously maintaining every component of the experiment at ultra-low, stable temperatures. With these precautions in place, they introduced subtle, precisely calibrated microwave pulses to delicately probe the circuit’s response, enabling highly accurate measurements of its electrical properties. Upon reaching extremely low temperatures, the system’s behavior perfectly aligned with the predictions of quantum tunneling theory.

How Did the Circuit Manifest Quantum Effects?

The team further investigated whether the circuit’s trapped state exhibited distinct, stepped energy levels—a defining characteristic of quantum systems—rather than a continuous range. They directed microwaves of varying frequencies onto the junction while fine-tuning the current. A remarkable observation occurred: when the microwave frequency precisely matched the energy difference between two allowed levels, the circuit would spontaneously escape its trapped state with greater ease. Higher energy levels correlated with faster escape rates. These findings conclusively demonstrated that the circuit’s collective state could only absorb or release energy in discrete “packets,” mirroring the behavior of an individual particle governed by quantum mechanics. Essentially, the macroscopic circuit behaved as a single, giant atom.

Cumulatively, these results established two pivotal facts. Firstly, a macroscopic electrical circuit—something visible to the naked eye—could undeniably exhibit quantum behavior, provided it was adequately isolated from environmental interference. Secondly, the key macroscopic coordinate within this circuit could be analyzed and understood using the established principles and tools of quantum mechanics.

What happens inside a superconductor?

| Photo Credit:

Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Crucially, these experiments also illuminated a practical pathway for manipulating and “reading” macroscopic quantum states. This involved precise control using a bias current, weak microwaves, and rigorous shielding against external radiation, providing a blueprint for dependable quantum measurements in solid-state devices. Following decades, particularly through the 1990s and 2000s, this foundational work led to the development of superconducting qubits, their integration into microwave resonators, and significant advancements in their coherence—the ability to preserve their fragile quantum states against environmental noise.

Revolutionary Applications of This Research

The technological ripple effects of this physics are profound. A circuit incorporating a Josephson junction can be engineered to emulate the discrete energy levels of an atom. Microwaves can then be used to precisely manipulate the circuit, causing it to “jump” between these energy states. By carefully linking the circuit to a resonator, scientists can even measure these changes without disturbing the delicate quantum state. This ingenious architecture, known as circuit quantum electrodynamics, forms the bedrock of many modern superconducting quantum processors.

(Think of a resonator as an echo chamber for microwaves. When the circuit is coupled to it, they can exchange energy in a controlled manner, enabling researchers to indirectly ascertain the circuit’s state by monitoring changes in the resonator’s behavior.)

Today, superconducting circuits leveraging macroscopic quantum effects are indispensable to a host of cutting-edge technologies. They function as ultra-sensitive quantum amplifiers, capable of boosting faint signals without introducing noise—a critical capability for both medical diagnostics and the search for elusive dark matter. These circuits enable measurements of current and voltage with unparalleled precision. Furthermore, they serve as microwave-to-optical converters, bridging quantum processors with fiber-optic communication networks, and are vital components in quantum simulators that meticulously model intricate materials or chemical reactions at the atomic level.

Ultimately, the utility of these devices stems from a fundamental characteristic: the circuit’s phase difference and the supercurrent respond to even the minutest external influences with significant, measurable changes. What might have once been considered a “bug” in the system, the laureates’ brilliant work transformed into a powerful and controlled feature.