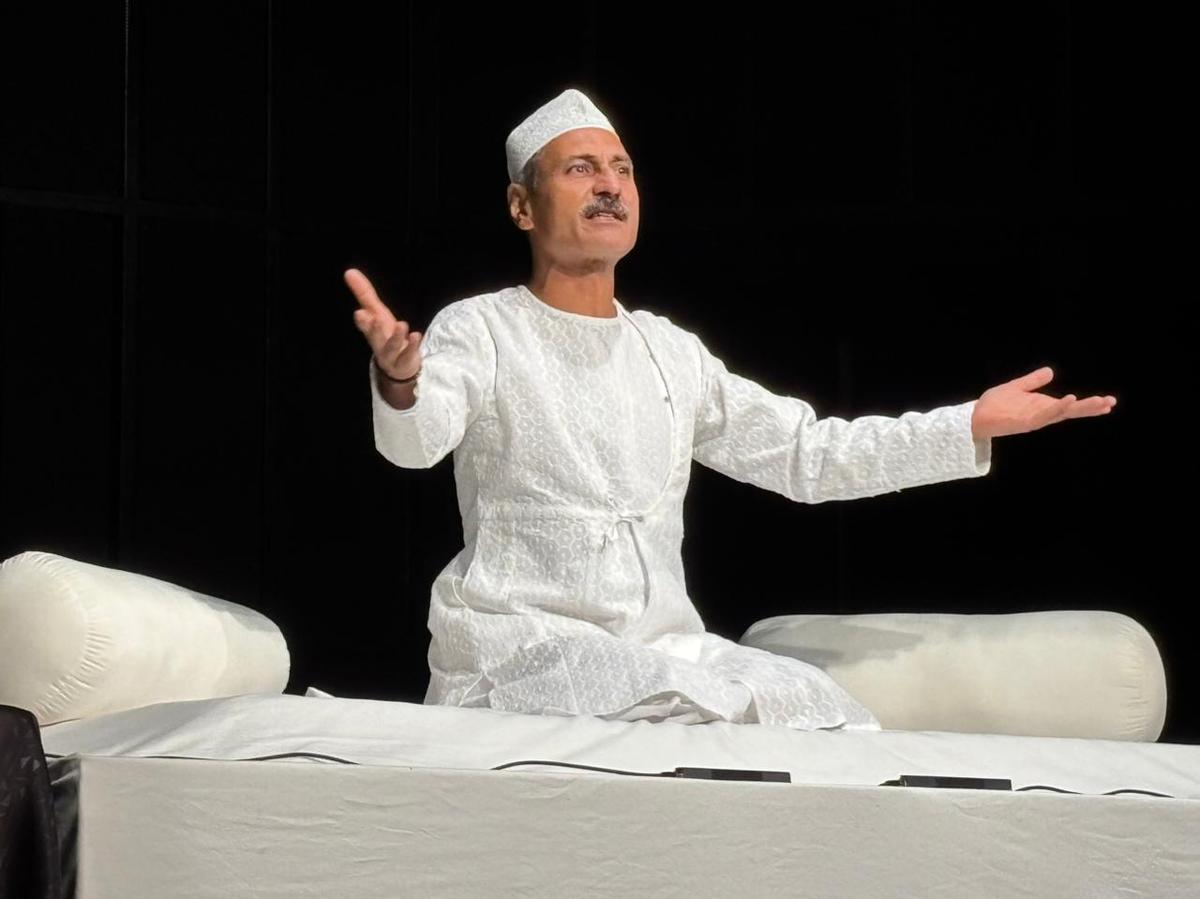

This year, as we celebrate the centenary of the legendary filmmaker Guru Dutt, many attempts have been made to understand the depth of his character, his profound loves, and his unique ability to blend meticulous research with raw emotion. Now, acclaimed storyteller Mahmood Farooqui takes on this challenge with his captivating Dastan-e-Guru Dutt. This evocative 140-minute performance, recently premiered at Delhi’s Habitat Centre and soon heading to Mumbai, offers a unique verbal portrait. The extensive research behind it will also be published as a 250-page book, with discussions even underway for a film adaptation.

The performance thoughtfully begins with a tribute to Guru Dutt’s subversive spirit, still relevant today. Farooqui encourages the youth to stay vigilant and rise against injustice with ‘Ae watan ke naujawan jaag aur jaga ke chal’ (from Baaz, 1951), concluding with a poignant celebration of the deep pain Dutt came to embody.

Farooqui has structured his compelling narrative into four distinct parts. He meticulously traces the evolution of Guru Dutt, exploring the psychological impacts of his parents and the early atmosphere of scarcity that molded his formative years. This period led him to pursue artistic aspirations under the guidance of the remarkable dancer-choreographer Anand Shankar. The dastaango then delves into the vibrant, often cutthroat ‘bloody bazaar of Bombay’ – P.C. Barua’s evocative description of Hindi cinema’s heart – where Dutt ultimately found his unique cinematic voice. The performance also delicately navigates his complex relationship with Geeta Roy and passionately celebrates his cinematic masterpieces.

“Everyone is a product of their time, and in Guru Dutt’s case, time was pivotal,” Farooqui observes. In his essay Classics and Cash, Guru Dutt offers a critique of a particular form of neorealism—perhaps subtly referencing Satyajit Ray—where filmmakers act as though Indian cinema didn’t exist before their arrival. Instead, Dutt championed pioneers like P.C. Barua and Devaki Bose, who crafted realistic films in the 1930s, unburdened by commercial pressures.

The cinema of the 1950s was deeply influenced by the progressive writers’ movement. “Through IPTA, film creatives learned how to tackle serious issues using popular storytelling idioms. There cannot be a Raj Kapoor without Shailendra and Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, and there cannot be Guru Dutt without S.D. Burman, Sahir Ludhianvi, and Majrooh Sultanpuri,” Farooqui explains.

However, the transition into the 1950s was far from a golden era, despite how it might appear in retrospect. The studio system was faltering, and the ‘film star’ culture was gaining prominence. The film industry increasingly became a vehicle for turning illicit wealth into legitimate gains for those who viewed it purely as a business. Narratives often revolved around themes of unity and separation, leaving little room to address critical issues like poverty, hoarding, black marketeering, unemployment, and evolving social customs.

Guru Dutt perceived this as a period of decline, attributing the shift to changes in the cinema-going audience. He grew up appreciating films like V. Shantaram’s Duniya Na Mane (1937), which advocated for women’s emancipation, and Gyan Mukherjee’s early blueprint for a Bollywood blockbuster, Kismet (1943).

Inspired by the oriental narrative style of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, Guru Dutt consciously avoided catering to European tastes. When Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam received a lukewarm reception at the Berlin Festival, he accepted it with stoicism.

Guru Dutt’s illustrious career can be divided into two distinct phases. Initially, he honed his technical prowess and mastery of song picturization with films like Jaal, Baazi, Aar Paar, and the production C.I.D, alongside the socially conscious romantic comedy Mr & Mrs ‘55. His trusted cinematographer, V.K. Murthy, once remarked that in Dutt’s films, songs were never incidental; they were integral to the narrative, with dialogues seamlessly leading into musical sequences.

In the second phase, he transformed his personal anguish and pain into cinematic poetry through masterpieces such as Pyaasa, Kagaz Ke Phool, and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. This powerful fusion of self-pity and melodrama forged a groundbreaking cinematic language. Farooqui draws a compelling link between the protagonists of both phases. The core character traits seen in Baazi, Aar Paar, and Mr & Mrs ‘55 echo in Vijay from Pyaasa, Suresh Sinha of Kagaz Ke Phool, and Chhoti Bahu of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. “They are not content with their current circumstances and strive for a better future without compromising their integrity—a clear reflection of Guru Dutt’s own personality,” Farooqui emphasizes.

Notably, Guru Dutt also followed a pattern of producing a critically acclaimed film after a commercially successful one. Pyaasa was preceded by C.I.D; Kagaz Ke Phool was followed by Chaudhvin Ka Chand; and Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam was succeeded by Baharen Phir Bhi Ayengi (which was released posthumously).

“What Guru Dutt struggled with was making low-budget films, unlike his contemporaries Ritwik Ghatak and Satyajit Ray. He attempted to make Gauri in Bengali, but it never saw a release. The box office, in a way, became a trap for Guru Dutt,” Farooqui reveals.

Satyajit Ray greatly admired Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, seeing it as a film that resonated with his own artistic sensibilities. However, Farooqui believes that a classical filmmaker couldn’t have created Pyaasa, a film that transcended niche audiences to connect deeply with the common person. “The same recklessness present in Pyaasa’s protagonist, the way he infused personal torment into a universal narrative, only Ritwik Ghatak could have achieved. In that sense, I see striking parallels between Guru Dutt and Ritwik Ghatak.” Born in the same year, both endeavored to express their lives through their films. At the same time, Farooqui adds, we must acknowledge that Guru Dutt benefited from the support of a star, his friend Dev Anand, and gradually gained popularity himself.

Farooqui’s insightful portrait of the master filmmaker draws on a multitude of sources, not all of them entirely adulatory. While Bimal Mitra’s reflections in Bichde Sabhi Bari Bari portray Guru Dutt with almost saintly reverence, Ismat Chughtai’s analytical dissection of his character in her novel Ajeeb Aadmi adopts a more critical stance. “The truth likely lies somewhere in between,” says Farooqui. He also incorporates Firoz Rangoonwala’s monograph on Guru Dutt, where the film historian hailed his films as cultural touchstones, and Nasreen Munni Kabir’s extensive scholarly work on the master.

Farooqui fearlessly examines Guru Dutt’s choices, particularly the disparity between the progressive themes in his films and his more conservative approach to his wife, Geeta Dutt’s, singing career. Geeta’s increasing struggle with alcohol and her suspicions regarding Guru Dutt’s relationship with Waheeda Rehman are also explored without reservation. Singing for Guru Dutt’s films effectively meant singing for Waheeda, a reality Geeta found unbearable, leading to deep fractures in their relationship. This tension culminated in Guru Dutt razing the bungalow he had built to the ground. Throughout these trials, Guru Dutt consistently turned his gaze inward, holding himself accountable for the turmoil within. Always driven by a sense of urgency on set, Farooqui suggests he seemed to be in a perpetual rush to embark on a new chapter in his life. “’Only the man of goodwill carries always in his heart this capacity for damnation and despair’ — this line from Graham Greene perfectly encapsulates Guru Dutt,” Farooqui concludes.