The story so far: Imagine particles effortlessly passing through solid objects, not by climbing over them, but by simply tunneling right through. This extraordinary phenomenon, known as quantum tunneling, is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics, typically observed at the nuclear and atomic scales. However, the 2025 Physics Nobel Prize honored John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis for their remarkable discovery: this same quantum behavior can manifest even in macroscopic electrical circuits, specifically those made of superconductors. Their groundbreaking work has unlocked immense potential for developing novel technologies that promise to revolutionize how we gather, analyze, and apply information about our world.

What is a Josephson junction?

At the heart of the trio’s Nobel-winning experiments lies a crucial component: the Josephson junction. This device consists of two superconductors separated by an extremely thin insulating layer. The scientists posed a profound question: could a characteristic of an entire circuit, such as the phase difference across this junction, mimic the behavior of a single quantum particle? Their meticulous experiments provided a definitive “yes,” revealing both macroscopic quantum mechanical tunneling and distinct, quantized energy levels within the circuit.

A schematic illustration of a single Josephson junction. It features two superconductors (A and B) separated by an ultrathin insulating layer (C).

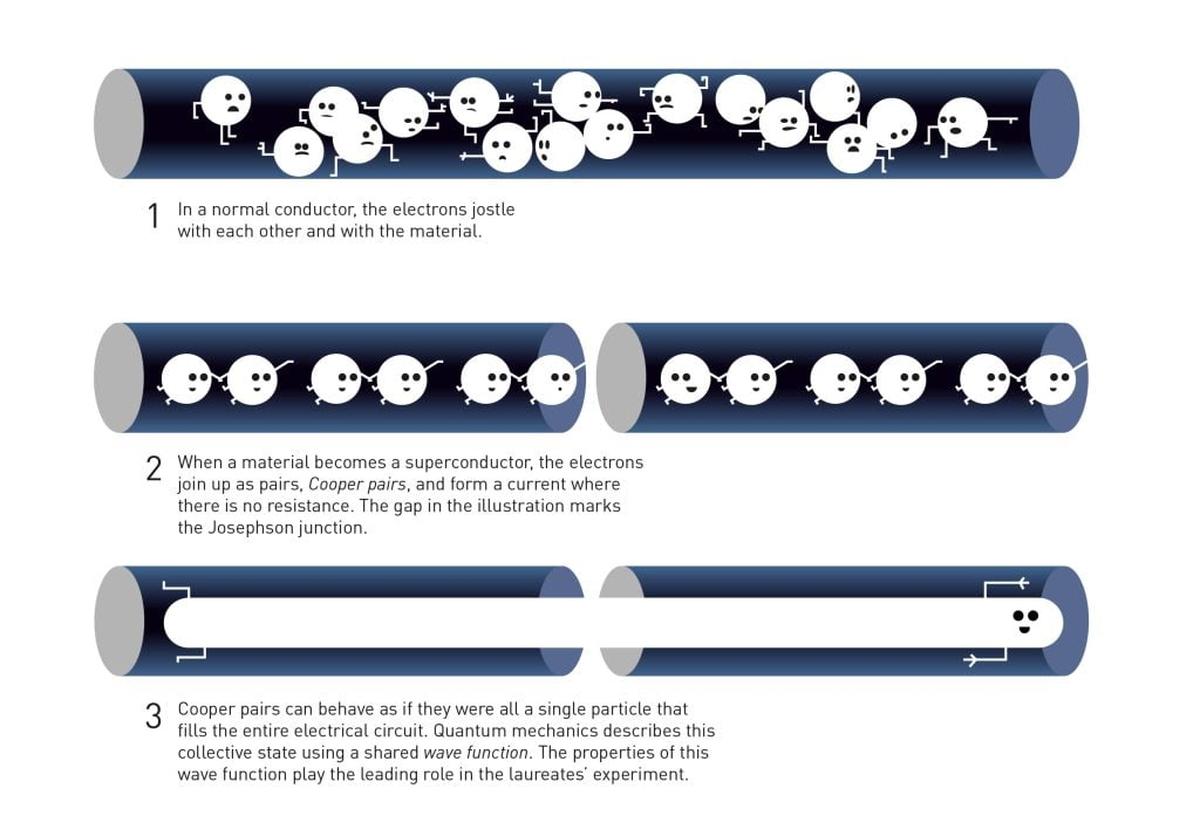

Within a superconductor, many electrons pair up and flow without any resistance. In the context of a Josephson junction, a crucial factor is the phase difference of the superconducting order parameter. This parameter is a macroscopic variable, shared by trillions of electron pairs within the material, that effectively defines the system’s state. Theoretical models indicate that the current passing through the junction is influenced by this parameter’s value, and the phase difference itself changes over time in response to the voltage applied across the junction.

When the scientists sent a current through the Josephson junction, they found that if it was small enough, the flow of paired electrons would halt, resulting in no measurable voltage across the circuit. Under classical physics, this “blocked” state would be permanent. However, the quantum realm dictates a different reality: the current possesses a slight probability of spontaneously tunneling out of this trapped state and flowing unimpeded, thereby generating a detectable voltage.

Why was the circuit fragile?

In the early 1980s, researchers intensely sought to confirm this tunneling phenomenon. They attempted to do so by adjusting the current and noting the point at which the junction produced a voltage. If electron pairs were merely escaping through thermal energy, similar to “jumping over a mountain,” then progressively cooling the device should lead to a higher current requirement to generate a voltage. Conversely, if true quantum tunneling was occurring, the rate at which electron pairs crossed the barrier would eventually become independent of temperature.

Despite the apparent simplicity of the experimental setup, a major hurdle was preventing stray microwave radiation from interfering with the circuit, which would distort the data and mask the temperature-independent behavior characteristic of quantum tunneling. Therefore, the researchers had to meticulously minimize and precisely characterize all environmental noise.

The Berkeley team, spearheaded by Clarke and collaborating with Devoret and Martinis, overcame this challenge by completely overhauling their experimental design to eliminate interference from stray signals. They employed specialized filters and robust shielding to effectively block unwanted microwaves, ensuring every component of the setup remained exceptionally cold and stable. Subsequently, they introduced subtle, precisely calibrated microwave pulses to probe the circuit’s response, enabling highly accurate measurements of its electrical properties. Upon reaching extremely low temperatures, the system’s behavior perfectly aligned with the predictions of quantum tunneling theory.

How did the circuit show quantum effects?

Further, the researchers aimed to ascertain if the circuit’s trapped state exhibited distinct, quantized energy levels, a definitive signature of a quantum system, rather than a continuous spectrum. To do this, they illuminated the junction with microwaves of varying frequencies while carefully modifying the current. A remarkable observation occurred: when the microwave frequency precisely corresponded to the energy difference between two allowed levels, the circuit dramatically accelerated its escape from the trapped state. This escape rate increased with higher energy levels. Such behavior unmistakably demonstrated that the circuit’s collective state could only absorb or release energy in discrete “packets,” mirroring the fundamental principle of a single particle governed by quantum mechanics. Essentially, the entire circuit functioned like an artificial atom.

A conceptual illustration depicting phenomena within a superconductor.

Collectively, these findings unveiled two pivotal insights. Firstly, a macroscopic electrical circuit — a device visible to the naked eye — could indeed exhibit quantum behavior when adequately shielded from its surroundings. Secondly, the crucial macroscopic property within that circuit could be analyzed and understood using the established principles and mathematical framework of quantum mechanics.

These experiments also illuminated a pragmatic approach for manipulating and observing macroscopic quantum states. This involved employing a bias current, weak microwave pulses, and rigorous shielding against external radiation. Their work provided a foundational template for conducting dependable quantum measurements in solid-state devices. Building on this, subsequent research in the 1990s and 2000s expanded these concepts, leading to the development of superconducting qubits, their integration into microwave resonators, and significant advancements in their coherence – essentially, their capacity to preserve fragile quantum states against environmental disturbances.

What are the applications of this work?

The technological implications stemming from this fundamental physics are vast. A circuit incorporating a Josephson junction can be engineered to emulate the quantized energy levels found in an atom. Microwaves can then be used to precisely control transitions between these energy levels. Furthermore, by carefully connecting the circuit to a resonator, researchers can indirectly measure changes within the circuit without disrupting its delicate quantum state. This ingenious design, termed circuit quantum electrodynamics, forms the bedrock of many modern superconducting quantum processors.

(Think of the resonator as a specialized echo chamber for microwaves. When the quantum circuit is linked to this resonator, they can exchange energy in a controlled manner. This interaction allows scientists to infer the circuit’s state indirectly, simply by observing the changes in the resonator’s behavior, thereby avoiding direct interference with the quantum system.)

Today, superconducting circuits leveraging macroscopic quantum effects are integral to a multitude of burgeoning technologies. They function as quantum amplifiers, capable of boosting incredibly faint signals without introducing additional noise – an invaluable capability for both advanced diagnostics and the elusive search for dark matter. These circuits are also employed to measure electrical current and voltage with unparalleled precision. Moreover, they serve as crucial microwave-to-optical converters, bridging quantum processors with high-speed fiber-optic networks. They are also vital components in quantum simulators, powerful tools used to meticulously model complex materials and even atom-by-atom chemical reactions.

In essence, these devices derive their utility from a key characteristic: the circuit’s phase difference and the supercurrent exhibit significant, measurable responses to even the most subtle external influences. What might have once been considered a challenge, the laureates brilliantly transformed into a powerful and advantageous feature.