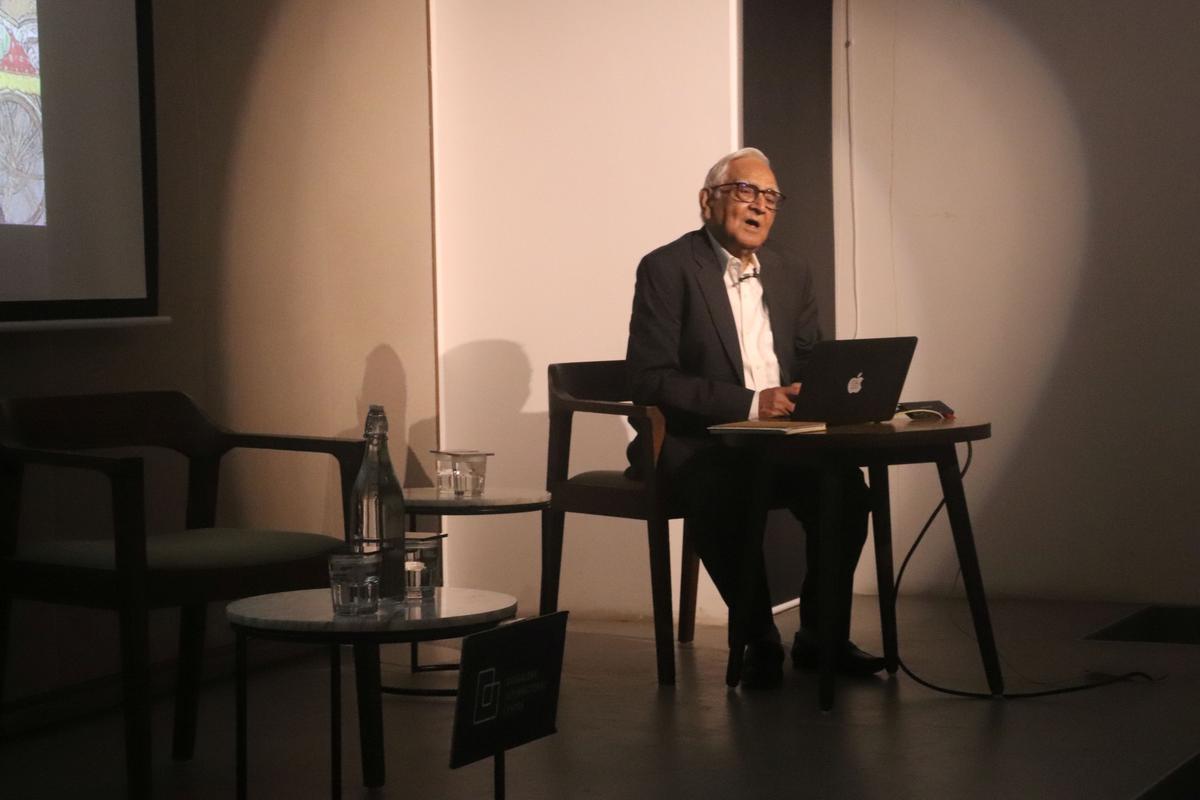

The Bangalore International Music & Arts Society’s golden jubilee festivities have been truly remarkable, featuring a series of enlightening events. Among them was the third ‘Heritage Lecture,’ delivered by renowned art historian and author Asok Kumar Das, titled ‘Music, Musicians, and Musical Instruments at the Mughal Court.’ This topic was perfectly suited for an organization dedicated to music.

Das, an expert in Mughal and Rajasthani art and culture, structured his talk into three compelling sections. He brought his extensive knowledge to life with stunning slides drawn from illustrated biographies of Mughal emperors, notably Shah Jahan’s Padshahnama. He also highlighted the Akbarnama, a historical account commissioned by Emperor Akbar (who was illiterate), meticulously documented by his courtier, Abu Fazl. Additionally, Das showcased the beautifully illustrated and inscribed imperial Ramayana and the Razmnama (a Persian translation of the Mahabharata, also known as ‘The Book of War’). These precious works, he noted, are fortunately housed in the Indian Museum, which boasts some truly extraordinary treasures.

During his extensive academic travels, Asok discovered rare Mughal miniature collections scattered across the globe, from Iran to Ireland and even Russia. He shared his fascination with how Mughal painting styles evolved and adapted under the distinct patronage of each emperor. He also highlighted the significant impact of Western art, noting that works by masters like Dürer and Delacroix were known and influential in the Mughal courts.

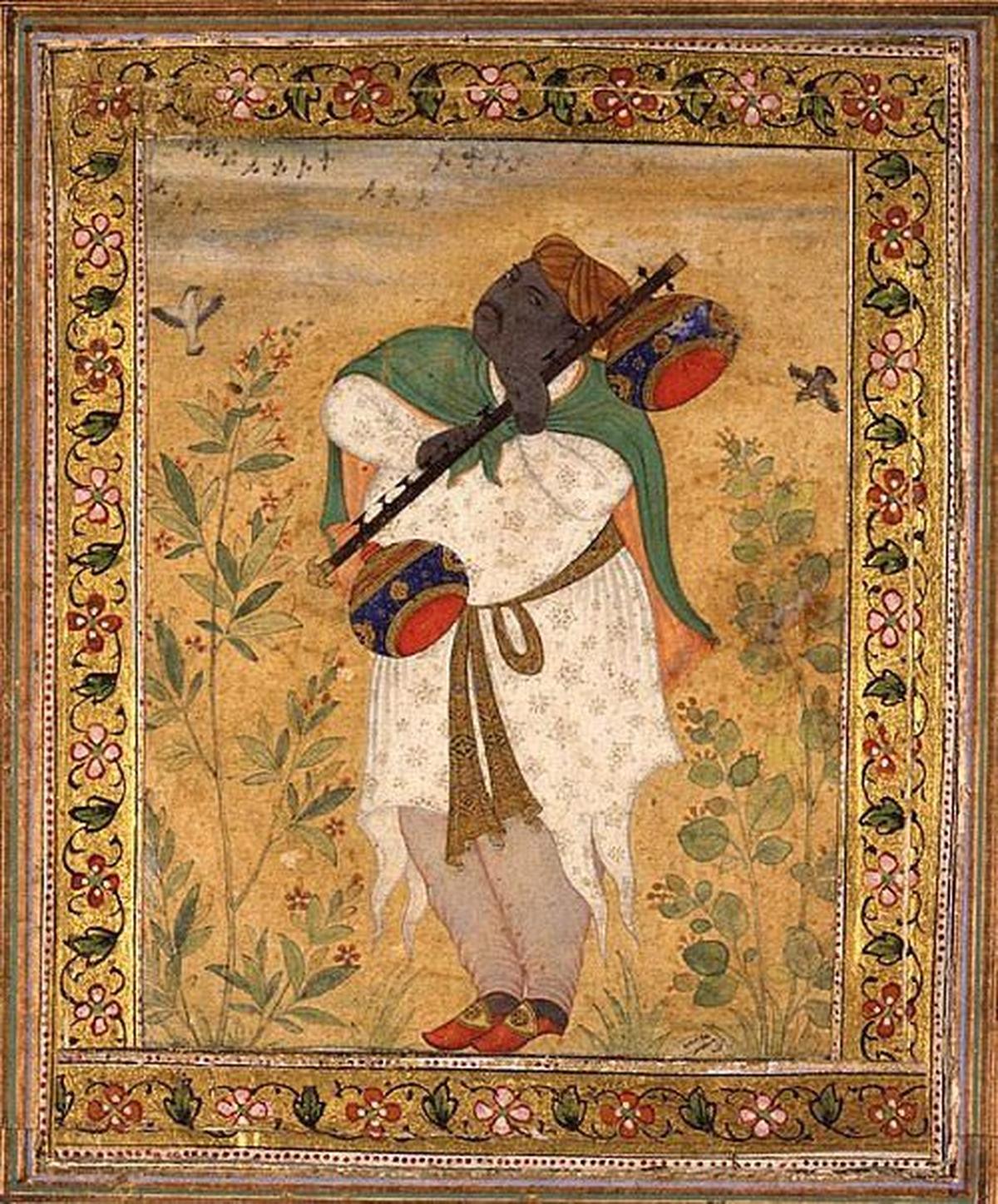

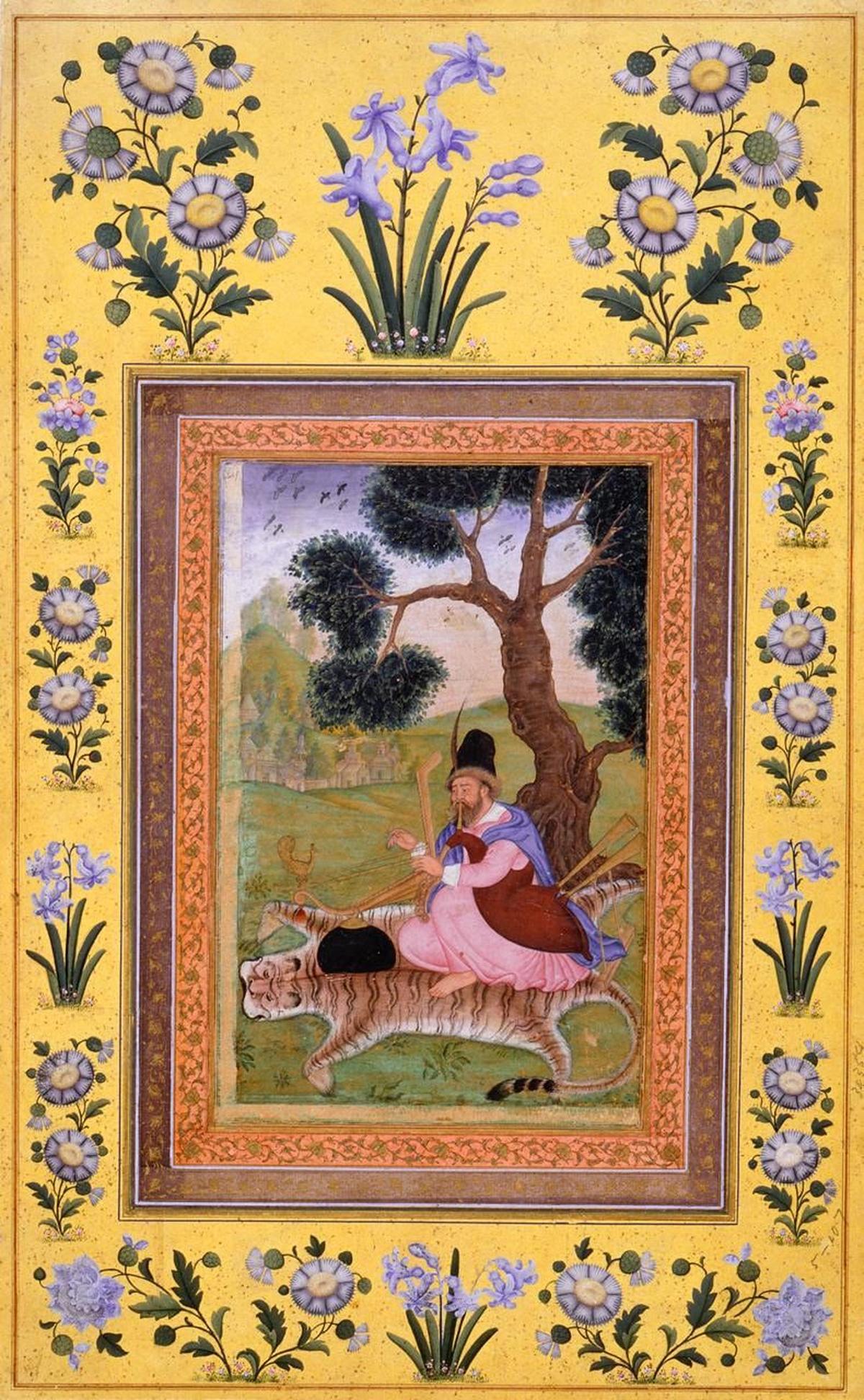

The miniature paintings themselves are of extraordinary quality, offering a lavish and detailed chronicle of the era. The precision is so remarkable that even the faces of onlookers can often be identified as portraits of actual courtiers. The musical scenes depicted are so vivid, one can almost imagine hearing the majestic blare of the shehnai and nafiri in grand durbars and processions, or the stirring rhythm of drums like the naqqara and tabla calling to battle and celebrating glorious triumphs.

Music was woven into nearly every aspect of Mughal life, from solemn prayers and rituals to joyous festivals, elaborate banquets, relaxing bathhouses, and even during hunts. The miniatures vividly portray various percussion, string, and wind instruments, many of which remain recognizable today. For instance, a slide depicting Naubat Khan clearly shows him with a been, identifiable as a rudra veena, while another painting titled ‘Plato’ appears to show him holding a harp.

Many of these exquisite miniatures employ a bird’s eye perspective, inviting viewers to “read” scenes unfolding on different levels. A prime example is ‘The Birth of Prince Salim,’ where the upper half illustrates the mother and newborn with attendants—including a drummer—on an adjacent terrace, offering glimpses into the zenana. The section below reveals another part of the palace, where the infant’s horoscope is being meticulously cast, alongside courtiers engrossed in a board game.

Intriguingly, the lowest sections of some paintings depict the common people, or ‘hoi polloi,’ celebrating with music and dance just beyond the palace gates. While vocalists and instrumentalists are clearly shown, their specific social standing within these scenes remains ambiguous. Despite music’s pervasive role in Mughal society, it’s noteworthy that direct mentions or depictions of the Ragmala series are conspicuously absent from these works.

Das emphasized that “Religion is but a part of Hinduism; its cultural roots delve much deeper, as emotions are profoundly embedded in the arts.” He explained that the Mughals truly adopted India as their homeland, with Babar being more than just a conqueror—he settled and built a legacy. This led to a harmonious cultural fusion: Mughals celebrated Hindu festivals like Holi and Diwali, and intermarried with Rajput women. India’s robust musical traditions were significantly enriched by the infusion of Mughal music, particularly with Sher Shah’s return from exile, bringing vibrant Iranian and Central Asian musical influences.

Despite his profound knowledge and extensive research, Asok remains refreshingly humble, passionately advocating for the widespread sharing of information. “Dissemination of knowledge is essential. What good is it if I know something and don’t share it?” he questioned, highlighting that historical images are invaluable educational tools for understanding our heritage. He lamented that many Indian institutions, despite possessing priceless collections, lack the necessary funding and resources to digitize and make these treasures accessible to the public.

This issue is particularly pronounced with miniatures, whose small size and intricate details make them challenging to appreciate fully in typical museum or gallery settings. In contrast, digital slides and close-ups offer a far more immersive and leisurely viewing experience, allowing for detailed examination.

Asok and his wife, Syamali, a respected textile historian, reside in Santiniketan. Their life there embodies the enduring ethos of “simple living and high thinking” that characterizes the Bengali liberal intellectual tradition.

Asok powerfully concluded, “Mughal culture is an enduring synthesis. You cannot simply erase our Islamic past by removing it from history textbooks. Its profound influence is visible even today in our food, costumes, music, art, and architecture. History isn’t created overnight, nor can it be annihilated so swiftly.”