“Yeh haath mujhe de de Thakur…” – iconic lines from films that almost faded into oblivion. Thankfully, the dedicated hands of film restorers and archivists are working tirelessly to rescue the fragile frames of classics like Sholay. This legendary movie is soon to be unveiled in a stunning 4K restored version, known as Sholay: The Final Cut.

Shehzad Sippy, CEO and MD of Sippy Films, reveals that Sholay: The Final Cut is the never-before-seen original, uncut version. For the first time ever, audiences will witness the film as it was truly intended. When Sholay premiered in 1975, the censor board, under the watchful eye of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, demanded a change to the ending.

The thought of a former police officer taking justice into his own hands by killing Gabbar was a major concern for the censors. Shehzad recounts how his grandfather, GP Sippy, attempted to reason with the ministry. However, with the film already three times over budget and three years in the making, a reshoot was ordered. This led to the altered version that has been seen for half a century. Now, all that is about to change, with previously omitted scenes, including Ahmed’s killing, being restored.

Shehzad is confident that this restored classic will draw audiences back to cinemas. He believes that the enduring themes of friendship and the battle between good and evil remain deeply relevant. ‘The younger generation, often exposed to less inspiring modern cinema, will finally grasp why this film is a timeless masterpiece,’ he states.

Classic Indian film posters, including Sholay, Do Bigha Zamin, Manthan, and Pakeezah, displayed alongside images depicting the intricate process of film restoration.

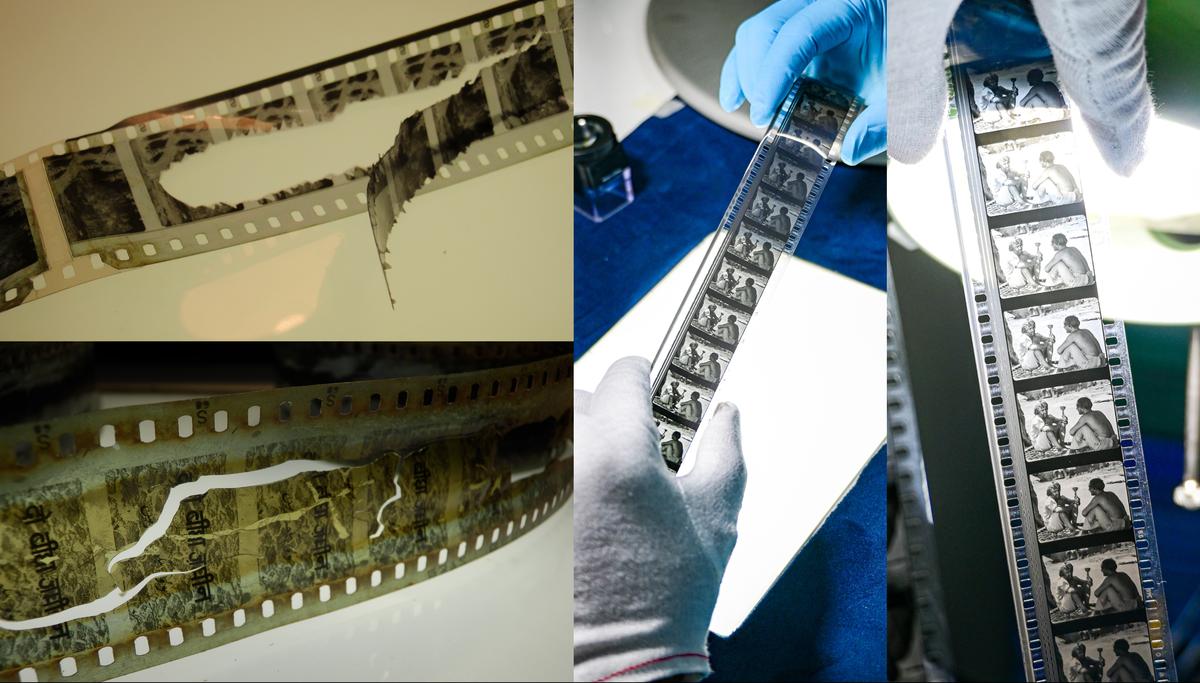

A powerful ‘before and after’ comparison of a Sholay film still, demonstrating the dramatic impact of restoration, along with images of the physical film reels being meticulously worked on.

At the heart of every film restoration project lies a captivating detective story. It’s a tale of passionate cinephiles embarking on a thrilling scavenger hunt for long-lost reels, driven by an unwavering commitment to preserve India’s rich cinematic heritage.

Even visionary filmmaker Guru Dutt, known for his relentless pursuit of perfection, would be astonished by the incredible journeys some films have taken. The original negative of Bharosa (1963), starring Dutt himself, was shockingly found in a scrap dealer’s shop, amidst old film magazines and forgotten VHS tapes. In other instances, reels of classics like Uttam Kumar-Vyjayanthimala’s Chhoti Si Mulaqat (1967) and Gulzar’s Maachis (1996) were discovered in Mumbai’s back alleys, haphazardly stacked against walls, sometimes even repurposed as household items.

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, the dedicated founder of the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF), has dedicated years to pursuing the ‘ghosts’ of Indian cinema. His relentless search for lost negatives, damaged reels, and mould-infested prints has taken him to the most unexpected places: bustling flea markets, forgotten warehouses, and decaying old movie theaters.

Dungarpur explains that the restoration process is meticulous: it begins with identifying the finest source material, followed by thorough inspection, cleaning, and delicate repairs. Each frame is then painstakingly scanned, with digital cleanup and color correction occurring in later stages. These efforts come at a significant cost, typically ranging from ₹35 to ₹50 lakhs per film, depending on the material’s condition. While Sholay‘s restoration is producer-funded, other projects benefit from contributions by esteemed organizations like Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, George Lucas’ foundation, and FHF.

However, the ‘sleuthing’ extends beyond technical tasks. Dungarpur emphasizes the critical importance of consulting surviving crew members. He meticulously searches for directors’ notes, personal diaries, lobby cards, song booklets, and shot breakdowns. ‘These invaluable resources provide crucial clues to fill in any informational gaps left by damaged or missing footage,’ he reveals.

The restoration of Sholay itself unfolded like a dramatic film. In 2022, director Ramesh Sippy and his son Rohan approached Dungarpur for help in locating the film’s negatives. They introduced him to Shehzad, who then began discussions about the restoration. Dungarpur vividly remembers, ‘He informed us that some of the film elements were stored in a Mumbai warehouse. Our examination of these film cans revealed the invaluable original 35mm camera and sound negatives.’

Shehzad subsequently informed FHF about further film elements, including the long-lost original ending, which his father, Suresh Sippy, had mentioned were stored at Technicolor in London before his passing in 2021. ‘The British Film Institute provided crucial assistance in assessing these reels, which were then carefully transported to L’Immagine Ritrovata, a specialized film restoration laboratory in Bologna,’ Shehzad recounts.

The eagerly awaited restored uncut version of Sholay making its debut at the prestigious Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna.

Among the most significant discoveries was the original four-track magnetic sound. Shehzad explains, ‘This format is ideal for preserving audio quality. We were incredibly fortunate to recover it in Mumbai, allowing us to reintegrate all the authentic, original sound back into the film.’

Dungarpur notes that this restoration, which primarily relied on interpositives found in London and Mumbai, was an incredibly complex undertaking, stretching over almost three years. The challenge was amplified by the severe deterioration of the original camera negative.

Meanwhile, the quest for other cinematic treasures persists. For Dungarpur, the ongoing restoration of Pakeezah (1972), projected to conclude within a year, carries a profound personal significance. His fascination with the film began in childhood, when his maternal grandmother, Usha Rani, Maharani of Dumraon, would reserve entire cinemas just for them. ‘I vividly recall watching Meena Kumari illuminate the screen in the iconic song ‘Inhi logon ne’,’ he shares.

Today, Dungarpur has crucial allies in producer Tajdar Amrohi and Rukhsar Amrohi, the children of Pakeezah‘s legendary director, Kamal Amrohi. The discovery of the film’s negatives itself sounds like a gripping Bollywood story. They chanced upon the reels in a laboratory while searching for another of their father’s classics, Daaera (1953). Rukhsar recounts, ‘Suddenly, there it was, in a deteriorated state, but thankfully still salvageable. The relentless city humidity certainly didn’t help.’

The original reel of Pakeezah, discovered in a severely deteriorated condition, showcasing the challenges of film preservation.

Tajdar reveals that the film’s prints were widely scattered, with each version varying slightly, even in runtime. He explains, ‘In earlier times, individual exhibitors would shorten films to accommodate more screenings. This practice has left us with a fragmented collection of mismatched reels and missing frames decades later.’

The Amrohi siblings entrusted FHF with the monumental task of reviving their father’s cinematic legacy, which is also destined for Bologna. Tajdar, balancing deep emotional ties with practical business sense, expresses his dilemma: ‘We are planning a strategic re-release, including a two-week theatrical run and festival screenings.’ He adds, ‘After restoration, we might even re-edit the film to better suit the pace and preferences of contemporary audiences.’

Close-up of the delicate process of restoring the reels of Pakeezah, frame by meticulous frame.

Tajdar remains hopeful that Pakeezah‘s timeless narrative will continue to captivate, a film whose real-life story was as poignant as its on-screen drama. He fondly recalls visiting the set as a 23-year-old, reflecting on the film’s arduous journey: ‘It endured so much – Meena Kumari’s declining health, my father and her separation in 1964 which paused production, and her unfortunate passing shortly after its release.’

A similar arduous journey marked the three-year restoration of Do Bigha Zamin (1953), a project spearheaded by Criterion Collection and Janus Films, in partnership with FHF. The team gained access to the original negatives, which the Bimal Roy family had entrusted to the NFDC-National Film Archive of India for preservation. Dungarpur describes the state of the film: ‘The elements had significantly deteriorated over time, suffering from extensive tears, mold damage, and heavy watermarks.’ Conservators meticulously repaired every section before shipping the reels to L’Immagine Ritrovata. A vital piece of the puzzle emerged when a combined dupe negative from the 1950s was discovered at the British Film Institute, proving instrumental in completing the film’s restoration.

The restoration of Do Bigha Zamin in progress, showcasing the intricate work involved in preserving this cinematic milestone.

Ultimately, these restoration efforts deliver a profound message: cinema, though inherently fragile, possesses an incredible capacity for endurance. Audiences are increasingly appreciating these renewed classics. Ashutosh Vyas, a 29-year-old graphic designer who experienced FHF’s restored Manthan (1976), noted how the film’s socio-economic themes remain powerfully relevant. ‘Today’s moviegoers are tired of formulaic stories. Learning that both director Shyam Benegal and cinematographer Govind Nihalani were involved in Manthan‘s restoration makes it even more impactful,’ he stated. For him, a restored Pakeezah would represent not just nostalgia, but a fresh discovery.

The esteemed late filmmaker Shyam Benegal, alongside Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, meticulously inspecting the restored reels of his iconic film, Manthan.

Ultimately, the revival of these cinematic treasures tells a compelling story: films, despite their on-screen grandeur, often face neglect behind the scenes. Yet, the relentless pursuit of their lost reels is a real-life drama, brimming with suspense, raw emotion, thrilling twists, and ultimately, a triumphant redemption.