Sumana Chandrashekar’s profound new book, My Journey with the Ghatam: Song of the Clay Pot (Speaking Tiger), transcends the typical memoir. It’s a critical and captivating journey into the intricate histories of Indian music, its performances, and its cultural memory. As Chandrashekar recounts her personal connection with the ghatam, she simultaneously challenges the very conventions of autobiographical storytelling. Beyond her individual experiences, she meticulously examines the wider social, gendered, and political forces that have dictated the ghatam’s position within India’s rich classical music heritage.

For generations, the ghatam, a distinctive clay pot percussion instrument, has been largely relegated to male musicians, often holding the “upa pakkavadyam” (secondary accompanying instrument) status within the strict hierarchies of Carnatic music. Sumana’s powerful narrative brings to light the voices that have historically been celebrated and, more importantly, those that have been deliberately suppressed. She challenges long-standing musical customs, highlighting practices that have faded into obscurity or been marginalized. This book masterfully explores the intricate interplay between personal memory and broader historical narratives. The ghatam itself becomes a potent symbol: an instrument of both resonance and quietude, prominence and periphery, reflecting the complex dynamics of patriarchy and power within the art form.

While the book delves into themes explored by previous musical analyses, it uniquely reveals how different perspectives illuminate varied truths. By re-examining history through the eyes of diverse, particularly women and marginalized, voices, it provides not only fresh insights but also essential tools to comprehend and engage with our present world with heightened empathy and understanding.

Breaking Stereotypes

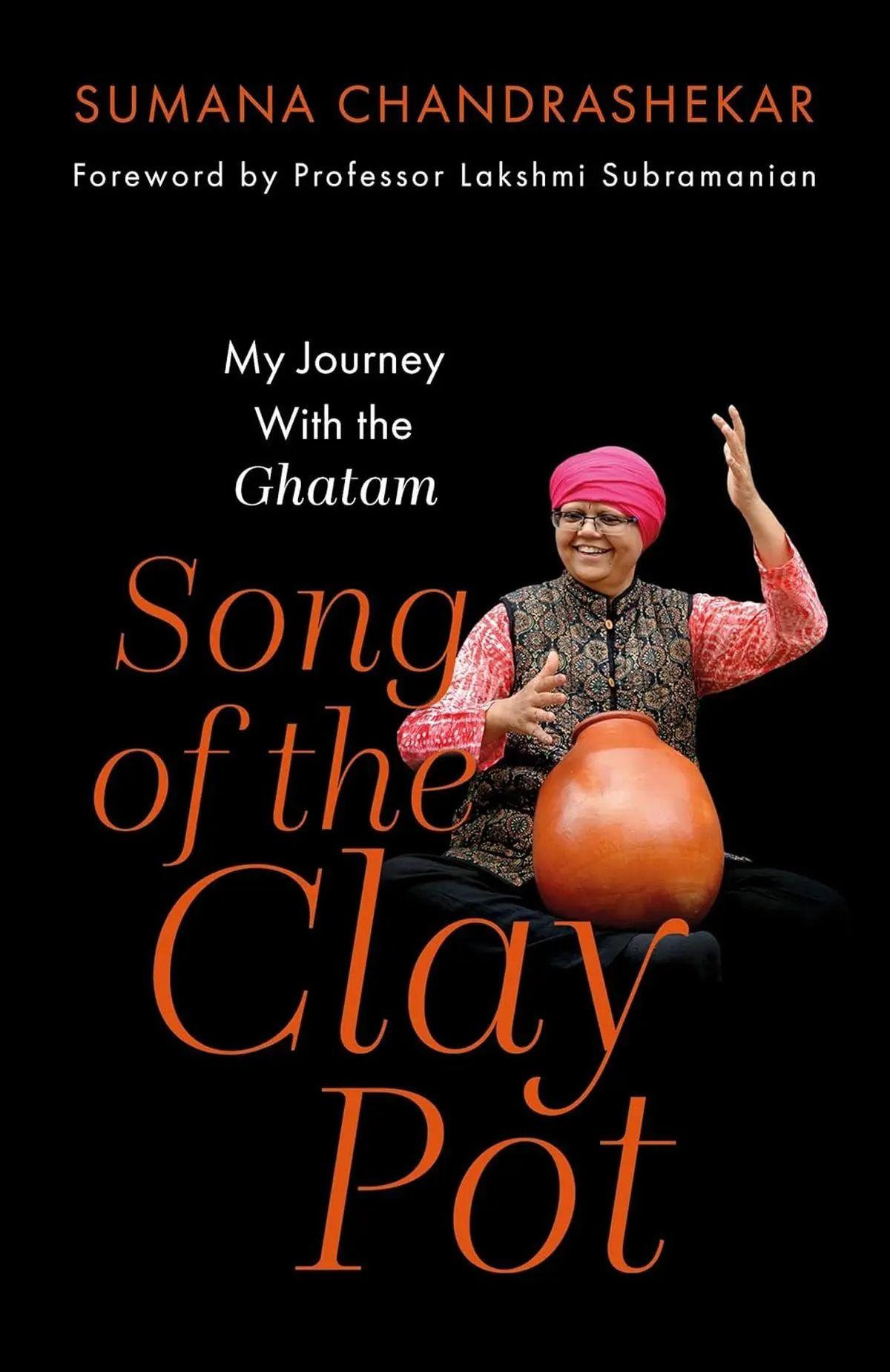

The compelling cover of the book, My Journey with the Ghatam: Song of the Clay Pot. | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

The book’s initial chapters meticulously trace Sumana’s introspective shift from Carnatic vocal music to embracing the ghatam, a pivotal change sparked by a recurring dream in the summer of 2008. She vividly details her journey with her guru, offering rich descriptions of her apprenticeship, the legendary percussionists who shaped the art, and the revered masters who paved the way. Her reflections are deeply heartfelt and often insightful, revisiting timeless themes of discipline, the physical demands of artistry, and the spiritual essence of music.

Under the masterful guidance of Sukanya Ramgopal, Sumana discovered not only a brilliant rhythm maestro but also a woman embodying quiet strength and profound humanity. Sukanya’s decision to pursue the ghatam was groundbreaking, occurring during a period when female percussionists were an extreme rarity and often faced outright hostility. Supported by two musical luminaries—Harihara Sharma and his son, Vikku Vinayakram—she stoically endured numerous dismissals and prejudices from established musicians and event organizers. Yet, none of these challenges diminished her unwavering dedication to the art. The narrative is infused with warmth and dignity, celebrating the influence of these three artists and their pivotal role in helping Sumana navigate a world steeped in bias. Their story prompts profound reflection on the intersection of gender and art, drawing parallels to the complex nattuvanar–Devadasi relationships of the past.

In stark contrast, the book presents the poignant story of Meenakshi from Manamadurai, a woman from a marginalized social background whose painstaking labor literally breathes life and sound into the ghatam. Her skilled hands meticulously craft the clay, ensuring its tonal perfection through days of arduous physical work. Yet, her invaluable contribution remains entirely unseen and unacknowledged by a world that reveres the instrument’s sound. Meenakshi toils in quiet contemplation, shaping the clay with intuitive precision. She notes that the media once sought her husband’s insights, and now her son’s; her own voice, however, remains perpetually unheard. Meenakshi’s narrative stands as a powerful counterpoint to Sukanya’s, illustrating a different form of devotion: creation without recognition, and dedication without visibility. It’s a stark reminder that the hierarchies within art extend far beyond the stage, reaching into the very creation of the sound itself.

Intriguing Questions

Sumana Chandrashekar, for whom the ghatam became a powerful conduit for her musical identity. | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Through these interwoven narratives, Sumana’s own identity slowly crystallizes, shaped by encounters with misogyny, patriarchal norms, and constant scrutiny over her appearance. Her perceptions of success and failure are often filtered through the world’s expectations. In contemporary times, she seems less equipped to confront emerging challenges, perhaps due to our modern inclination to believe the world should be inherently fair and just, despite its persistent inequalities. This realization gives rise to one of the book’s most profound questions: Sumana recalls that the legendary M.S. Subbulakshmi was a skilled mridangam player before becoming a vocalist. Had Subbulakshmi continued as a percussionist, how might the trajectory of women in percussion have changed? This question deeply resonates with Sumana, who finds herself torn between continuing her journey with the ghatam and abandoning it, until her guru wisely reminds her that an artist’s true sustenance comes not from external validation, but from an unyielding ‘inner fire.’

The concluding chapters of the book showcase meticulous research, with sections like ‘Musical Censorship,’ ‘The Phoenix Rises,’ and ‘On Pot Bellies’ providing particularly captivating insights. Drawing from a rich array of sources, Sumana presents her findings with remarkable thoughtfulness. For example, she highlights the re-emergence of the semi-circular concert seating arrangement, a historical practice that not only challenges traditional stage hierarchies but also facilitates direct eye contact between the upa pakkavadyam artist and the main performer, thus remedying a subtle yet significant disadvantage. Such insightful observations are abundant throughout the book.

From our current vantage point, however, it’s crucial to approach our conclusions with a degree of circumspection. This is precisely why we must continually re-examine history. The book encourages us to reflect not on simplistic distinctions of right and wrong, or on an entirely inflexible and insensitive social structure, but rather on the profound complexities that extend beyond our immediate comprehension. It reveals instances where gender and hierarchy were momentarily set aside, and genuine artistic collaborations flourished. Yet, these moments existed alongside significant absences, unexplored gaps, and unspoken tensions—patterns whose underlying causes may remain elusive. This calls us to resist drawing facile conclusions. In this profound sense, the book presents a subtle, yet deeply penetrating question: how do we truly engage with that which is partly seen, partly felt, and perpetually lived?

Ultimately, this memoir powerfully asserts the necessity of continuously revisiting cultural narratives, not to undermine tradition, but to unveil its multifaceted layers and, in doing so, to pave the way for a more inclusive and equitable future in music.